Markets don’t function well if

they are ridden with frictions like lack of information or lack of

trust. A new working paper finds that cities in the sixteenth century

where monopolies of densely networked merchant guilds declined had

significantly higher levels of printing, as they were early adopters of

printing technology. Additionally, these cities were found on the

Atlantic coast, where traders had the greatest incentives to form new

connections with unfamiliar traders.

In the sixteenth century, the Northwest

European region of England and the Low Countries underwent

transformational change. In this region, a bourgeois culture

emerged and cities like Antwerp, Amsterdam, and London became centers

of institutional and business innovation, whose accomplishments have

influenced the modern world.

For example, one of the first permanent

commodity bourses was established in Antwerp in 1531, the first stock

exchange emerged in Amsterdam in 1602, and joint stock companies became a

promising form of organizing business in London in the late sixteenth

century. The sixteenth century transformation was followed by the

seventeenth century Dutch Golden Age, and the eighteenth century English

Industrial Revolution. What made the Northwest region of Europe so

different? The question remains a central concern in social sciences,

with scholars from diverse fields (Weber, 1905; North, 1990; Padgett and Powell, 2012; McCloskey, 2016; Rubin, 2017) researching the subject.

The medieval power of merchant guilds

Markets don’t function well if they are

ridden with frictions like lack of information, lack of trust, or high

transaction costs. In the presence of frictions, business is often

conducted via relationships.

Until the end of the fifteenth century,

impartial institutions like courts and police that serve all parties

generally—so ubiquitous today in the developed world—weren’t well

developed in Europe. In such a world without impartial institutions,

trade often was (is) heavily dependent on relationships and conducted

through networks like merchant guilds. Such relationship-based trade

through dense networks of merchant guilds reduced concerns of

information access and reliability. Not surprisingly, because the

merchant guild system was an effective system in the absence of strong

formal institutions, it sustained in Europe for several centuries. In

developing countries like India, lacking in developed formal

institutions, networked institutions like castes still play an important

role in business.

Before the fourteenth century, merchant

guild networks were probably less hierarchical, more voluntary, and more

inclusive. But, with time, merchant guilds started to become exclusive

monopolies, placing high barriers to entry for outsiders, and they began to resemble cartels with close involvement in local politics. There were two reasons why these guilds erected such tough barriers to entry:

-

Repeated committed interaction was the key to effectiveness of merchant guilds. Uncommitted outsiders could behave opportunistically and undermine the reliability of the system. Therefore, outsiders faced restrictions.

-

Outsiders threatened the position of existing businessmen by increasing competition. So, even genuinely committed outsiders could be restricted to enter as they threatened the domination of existing members.

But, in the sixteenth century, the

merchant guild system began to lose its significance as more impersonal

markets, where traders could directly trade without the need of an

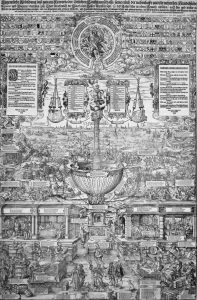

affiliation, began to emerge (see Region 1 of map in Figure I) and

rulers stopped granting privileges to merchant guilds. The traders began

to rely less on networked and collective institutions like merchant

guilds, and directly initiated partnerships with traders who they may

not have known well. For example, in Antwerp the domination of intermediaries (called hostellers)

who would connect foreign traders declined. Instead, the foreign

traders began to conduct such trades directly with each other in

facilities like bourses.

Emergence of markets in the 16th century

A new working paper studyies the emergence of impersonal markets in Europe during the

sixteenth century. The author surveys survey the 50 largest European cities during the

fourteenth through sixteenth centuries (mapped in Figure I) and codify

the nature of sixteenth century economic institutions in each of the

cities (explore interactive data on early modern Europe).

In the survey, I find that merchant guilds were declining in the

Northwest region of Europe, while elsewhere in Europe they continued to

dominate commerce until much later, although there were some reforms

underway in the Milanese and Viennese regions of Italy.

What explains the observed pattern of

emergence of impersonal markets in sixteenth century Europe? I focus on

the interaction between the commercial and communication revolutions of

the late fifteenth century Europe. In the paper, I argue that the

Northwest European region uniquely benefited from both of these

revolutions due to its unique geography.

Commercial revolution at the Atlantic coast

What motivated traders to seek risky

opportunities beyond close networks? If traders found partnerships with

unfamiliar traders beyond their business networks to be highly

beneficial, that would provide good incentives for the rise of

impersonal markets. The Northwest Region was close to the sea, notably

the Atlantic coast, which was at the time undergoing a commercial

revolution with the discovery of new sea routes to Asia and the

Americas. So, the region became a hub for long distance trade,

attracting unfamiliar traders who came to its coast looking for business

opportunity. I find that all cities where merchant guild privileges

declined were at the sea, along the Atlantic or North Sea coast.

Moreover, all cities where merchant guilds underwent reform (but didn’t

decline) were within 150km of a sea port.

The communication revolution of the postal system and the printing press

What made traders feel confident about

the reliability of such risky impersonal partnerships? If availability

of trade-related information and business practices improved, it could

increase confidence traders had in such unfamiliar partnerships. In the

sixteenth century, the postal system improved across Europe.

The postal system made communication between distant traders easier as

traders could correspond regularly with each other and gain more

accurate information. This helped expand long distance trade across

Europe.

While the Northwest European region

didn’t have a particular advantage over other regions in postal

communication, it had an advantage in early diffusion of printed books.

The Northwest European region was close to Mainz, the city where

Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable time printing press in the mid

fifteenth century. Dittmar (2011)

showed how cities close to Mainz adopted printing sooner than many

other regions of Europe in the first few decades of its introduction.

So, trade-related books and new (or unknown) business practices like

double-entry bookkeeping diffused early and rapidly in the region.

Such a high penetration of printed

material reduced information barriers and improved business practices. I

find that all cities where guild privileges declined or merchant guilds

underwent reform in the sixteenth century enjoyed high penetration of

printed material in the fifteenth century. Among cities within a 150km

distance from a sea port, cities where merchant guilds declined or

reformed had more than twice the number of diffused books per capita

than cities where merchant guilds continued to dominate.

As a comparison, there were four major

Atlantic port cities where merchant guilds declined: Hamburg, London,

Antwerp, and Amsterdam; while there were four guild-based Atlantic

cities: Lisbon, Seville, Rouen, and Bordeaux in the sixteenth century.

The fifteenth century per capita printing penetration of the cities

would stack as: Lisbon < Bordeaux < Hamburg < Seville < Rouen < London < Amsterdam < Antwerp.

The combination of both the commercial

revolution along the sea coast, especially the Atlantic coast, and the

communication revolution, especially near Mainz, uniquely benefited

Northwest Europe, as it began to attract traders who favored impersonal

market-based exchange over exchange conducted via guild networks. Rulers

began to disfavor privileged monopolies when they realized the

feasibility of impersonal exchange and that they could have superior

sources of revenue from impersonal markets. In the region, trade democratized, as more people could participate in business.

Regions like Spain and Portugal that

benefited only from the commercial revolution of trade through the sea

to Asia and Americas had low levels of printing penetration. In

contrast, regions like Germany, Italy, and France benefited from the

communication and print revolution but didn’t enjoy a bustling Atlantic

coast. Thus, no other region enjoyed the unique combination of both

benefits of the commercial and communication revolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment