LISBON.-

The history of this exhibition begins in April of 1866, when the

pre-Raphaelite painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) left

his home in Chelsea, London, to evaluate a painting he had seen in a

small antique shop. “A large landscape with about 120 figures of the

school of Velasquez, [but] not, [I think], by the great V himself”,

wrote the painter. The British art world had awakened to Spanish

painting and collectors were on the lookout for works by great masters

such as El Greco, Velázquez and Goya. Despite not recognising the city

represented in the painting, Rossetti correctly guessed at its Iberian

origin.

An

impetuous and eclectic collector, Rossetti divided the canvas into two,

probably because it did not fit on the already overcrowded walls of his

London home. It is known that Rossetti took these two canvases with

him, along with other works of art, when he went to live at Kelmscott

Manor (Oxfordshire) with the painter William Morris (Rossetti and Morris

shared this house for some months in 1871 and between 24th September,

1872 and July 11th, 1874). It is also known that the two paintings

remained in Kelmscott Manor when Rossetti was forced to leave the house

suddenly after a problematic love affair. They were later included in

William Morris’ assets.

An article by Julia Dudkiewicz (“Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s

collection of Old Masters at Kelmscott Manor” in The British Art

Journal, vol. XVI, No. 2, 2015) confirms that these two paintings

belonged to Rossetti’s collection. The historian reports that in May

Morris’ (18621938) will – daughter of William Morris and heiress of

Kelmscott Manor – a list of 220 objects is attached, with descriptions

that encompass their provenance. The list includes the two paintings:

“two pictures of scenes in a city, part of D. G. R.’s things”.

The paintings (currently owned by the Society of

Antiquaries of London) have remained at Kelmscott Manor since the 19th

century but the represented city was only identified in 2009, by

Annemarie Jordan Gschwend and Kate Lowe. The first clue that led to its

identification was the number of black people portrayed; in 16th century

Europe, only Lisbon and a couple of Spanish cities had such a large

percentage of Africans. The architectural details such as the tall

narrow houses, the covered gallery with marble columns – 149 in total –

and the iron railings led Lowe and Jordan to conclude that it was

Lisbon. And, more specifically, Rua Nova dos Mercadores, Lisbon’s main

trade street in the 16th century, full of merchants, acrobats,

musicians, travelling salesmen, knights, jewels, silks, spices, exotic

animals and other wonders imported from Africa, Brazil and Asia.

This exhibition aims to reconstitute the heart of Lisbon

during the Renaissance with 249 pieces belonging to 77 lenders: 64

national (institutions and private collections) and 13 international

(two private collections and 11 institutions, among them the British

Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum, Museo Nacional del Prado, Leiden University

Libraries and Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico “Luigi Pigorini”).

On display for the first time in Portugal, the two

paintings representing Rua Nova dos Mercadores open the first of the

exhibition’s six sections: “Lisbon City Views: historical background”,

“Novelties”, “From Africa”, “Shopping in Rua Nova”, “Animals from other

worlds” and “Simão de Melo’s house”.

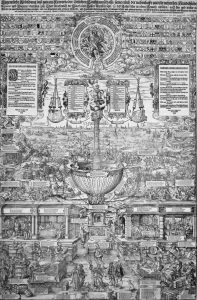

Of note within this surprising set of never before

assembled pieces are the extraordinary and meticulous Panoramic View of

Lisbon, c. 1570- -1580 (Leiden University Library), the Reliquary Casket

containing the relics of Saint Vincent (Patriarchal Cathedral -

Treasure, Lisbon), the View of Lisbon waterfront with the royal palace,

the Paço da Ribeira, 1505 (Câmara Municipal de Cascais/ Condes de Castro

de Guimarães Museum), the Euclidis Megarensis Philosophi atque

Mathematici [...], mathematical works by Francisco de Melo, 1521

(Stadtarchiv der Hansestadt Stralsund), Terrestrial Paradise by Pieter

Brueghel the Younger (Museo del Prado), Processional Cross belonging to

Catherine of Bragança containing the relics of Saint Thomas Becket (Vila

Viçosa Ducal Palace) and the 1579 cameo, by Jacopo da Trezzo,

representing King Manuel I’s rhinoceros (Guy Ladrière Collection).